“Dumuzi went out to the sheepfolds;

He lay down among the sheepfolds.

He caused the sheepfolds to multiply;

He made the sheep give birth to twins.”

In this passage, Dumuzi’s ability to increase the fertility of the sheepfold is compared to the virility of a wild ram. The comparison reinforces the idea that Dumuzi is powerful and virile. While it is certainly an interesting idea of an aphrodisiac, rather than wax poetic about the demon Humbaba or the virility of Dumuzi, let us turn our attention to the captivating works of Sappho, the Greek lyric poet who lived some 2600 years ago.

Come now to me, and release me from this pain,

and everything my heart longs to have accomplished, accomplish.

You be my ally.

And in this battle, fight by my side.

Serve me a cup brimming full with that wine

which sets the nerves on fire.

— Sappho, Hymn to Aphrodite

One cannot help but wonder if Sappho was referring to a wine infused with a certain mushroom, a concoction that would awaken the senses and transport the drinker into a world of heightened awareness and mystical experience. It is a tantalising idea, for this is a most peculiar combination of events, for normally when one’s nerves are on fire, far from being a painkilling event, it is rather the cause of the pain. The only substance I can think of that would cause fiery nerves to be a painkiller? Our wonderful Empress of mushrooms.

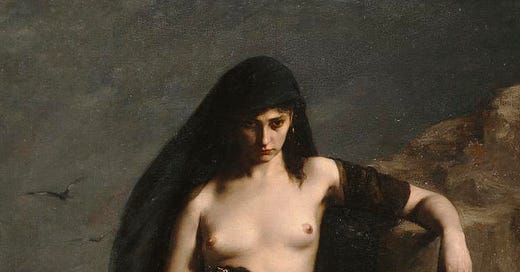

Curiously, as with Heraclitus, post-medieval representations of Aphrodite tend to be rather depressing in tone. It could be that the ‘erotic’ was seen as something dark in itself by the late Victorian period. And we might also conclude that Mengin had a rather depressing idea of the dimensions of the lyre itself, or of her hands or toes for that matter, so we’d better look a little earlier to the Neo-Classicists, although Umberto Eco rightly points out in his book History of Beauty when he discusses this painting:

Mengin’s Sappho is exemplary of the type of beauty that develops in the context of Romanticism, a beauty that seeks out the effects of light and color to suggest depth and mood. The Sappho does not offer us a single model of a face or of a body. It offers us a blaze of colors and textures, a play of glimmerings, a surface that shimmers like an opal or that becomes as soft as silk.

(Chapter 6, p. 206)

Charles Mengin, Sappho, 1877

(Plate 68)

Yes, Umberto, you are right. Nevertheless, let’s go back in time and take a look at a curious legend, depicted by the neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David.

Phaon is a figure from Greek mythology, most famously associated with the ancient Greek poet Sappho. He is said to have been a ferryman from the island of Lesbos. According to legend, Phaon was an old man when he met the goddess Aphrodite in disguise. Unaware of her true identity, he agreed to ferry her across the sea for free. In gratitude for his kindness, Aphrodite revealed her true form and granted him youth, beauty, and immortality.

Unfortunately, most of Sappho’s luminous poetry has been lost.

But there is a deer in her poems.

In Anne Carson’s translations, one fragment reads:

... limping after you

as a limping deer after

the prints in the deep-pressed snow

Sappho lived 2600 years ago, just a generation before Heraclitus.

The world was a very different place then. It was a time when zebras, tigers, and even lions roamed the wilds of ancient Greece—

a landscape so radically different from the one we imagine today that it defies easy comprehension.

It is all too easy for us to fall into the trap of imagining the past as a cheap reproduction of our own time, populated by people dressed only slightly differently from ourselves. But to do so is to miss the true depth and richness of the ancient world— a world as complex and nuanced as our own, but with its own unique wonders and mysteries.